Security

Introduction

Security lacks the lustre of liberty – or equality or fraternity/sorority. It feels like a virtue of withdrawal, of shelter, whereas the others are virtues of openness and momentum. When we talk about security, we may mean the condition that allows us to be or to feel protected from danger and risk, or perhaps which offers the opportunity to prevent, eliminate or reduce the severity of harm, difficulties and unpleasant, annoying, distressing or damaging events. In the Roman Empire, Securitas was the goddess who guaranteed public and private security. She was depicted on coins, surrounded by four attributes – the throne (hegemony of Rome), the lance (battling enemies), the cornucopia (prosperity) and the palm frond (a peace offering) – and leaning against a column, in a posture that was meant to symbolise calm and "quiet strength". But the very word securitas is a curious one: made up of sine ("without") and cura ("care"), it appears to refer to a meaning that contradicts that evoked by security, which is not generally understood as a lack of care, consideration or attention. So, as suggested by Tacitus in his Historiae, should we see something "inhuman" (inhumana securitas) in the sense that the absence of care or attention is, in reality, an absence of anxiety, a guilty indifference to the deployment of violence (the civil war in Rome in 69), even a degree of blindness in distinguishing right from wrong or a total lack of a sense of responsibility – factors which, combined, enable the flourishing of... insecurity and the risks of danger? With two sides, securitas both "lets it happen" and "takes care of it", in other words she seeks to neutralise both the elements of disorder, atrocities and conflicts, and the "irresponsibility" that makes them efficient. It is this latter sense which prevailed, and allowed securitas to meet libertas.

Almost the entire history of philosophy, from Machiavelli to Hobbes, from Locke to Montesquieu, from Smith to Bentham, from Marx to Foucault, has attempted to conceptualise the link between security and liberty, stressing the need for balance between the two concepts. If security is too heavy, this risks a drop in liberty; extreme promotion of liberty risks blocking the functions of security – understood as an individual right, as social security (all activities associated with social policy: supervision of labour, income, health, environment, urban planning and construction, transport, communications, education, culture, free time, etc.) and as national safety or "security".

The complex link between liberty and security is apparent in various forms throughout modern constitutionalism. The first North American Constitution (Virginia, 1776) guaranteed security for the purposes of something even more desirable than liberty: happiness. Meanwhile the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen in 1789 proclaimed that the goal of any political association was the protection of the natural and imprescriptible rights of man: liberty, property, security and resistance to oppression. In contrast, the Thermidorian Declaration of 1795 appears more "left-wing", considering security to be "the result of everyone working together to secure everyone’s rights". In other words, ensuring security is not about harming liberty, but about making it possible, in a way that is certainly more difficult than an approach that allows insecurity to make it challenging. But what limits can be put in place between security and "total security", between legitimate protection and the panoptic obsession with control that takes over states when emergency situations, such as pandemics or terrorist attacks, occur?

Robert Maggiori

© Les Rencontres Philosophiques de Monaco (Monaco Philosophical Encounters)

Informations

Similar events

Raconte-moi...un conte sur les animaux + 4 ans

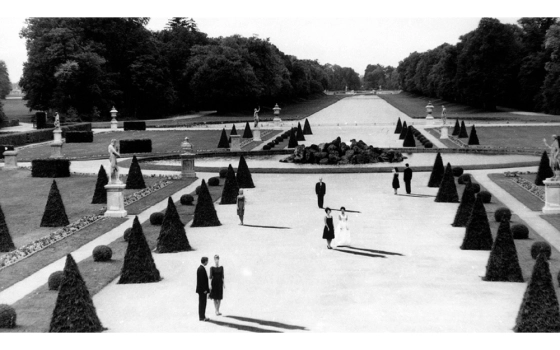

Nocturne et projection de "L'Année dernière à Marienbad" (1961) d'Alain Resnais