Philosophy workshop: what does it mean to be in love?

We would like to invite you to a philosophy workshop presented by Alicia Gaudel, who leads philosophy workshops for adults and children.

Introduction

What is a philosophy workshop?

It is a discussion between children, but not just any discussion.

Drawing on a story, a cartoon or a work of art, the children have a free discussion among themselves about a philosophical issue. There is a lot to say about this issue, and that’s why children enjoy philosophising so much.

Say what you think and think what you say

During a philosophy workshop, there is never any attempt to impose a single way of thinking on children. Quite the contrary: with the help of an experienced workshop leader, budding young philosophers learn to reflect, to listen to others and to express their own ideas. Philosophy workshops are an exercise in listening, and offer children the opportunity to better understand themselves while developing tolerance for other people and their differences.

"There’s no such thing as love, only proof of love". Jean Cocteau

Philosophy workshop: what does it mean to be in love?

Love: the whole world is talking about it, but what is it, really? We could begin by saying that love is something strong, something that can make us feel happy, sad, or even a bit lost. We can also say that there are several kinds of love: the love we feel for our family, our friends or even for a pet. But there’s also the love we have for skiing, chocolate or reading! So to avoid any confusion, in this workshop we are asking a more specific question: what does it mean to be in love? It is a feeling which sometimes seems obvious, and at other times so mysterious. We recognise it when it is there, but it is so difficult to explain.

When we are in love, we can feel attracted to a person, as if they are exercising an invisible force, a little like a magnet. Where does this feeling come from? Does it happen to everyone? Can we explain why one person attracts us and not another? Are the explanations that we find solid, and do they work for everyone?

Romantic relationships can also be associated with desire. A particular need to get closer to the other person, to be with them in a unique way. But what is desire, ultimately? Is it always part of love? Can it disappear or change over time? Is it possible to love someone without desiring them?

Finally, to love sometimes means to want the best for the other person, to want this to the extent that we will put our own wishes to one side. Does loving mean forgetting ourselves a little? Are there any limits to this? Can we be in love while still asserting our own needs? What do you think is important to understand when it comes to “wanting the best for another person”?

In this workshop, we will discuss the questions raised by love between two people. We will seek to understand what makes up a romantic relationship: attraction, desire and this mysterious balance between ourselves and the other person. It will be an opportunity to explore and reflect on these feelings which are a part of life.

The workshop for children will be held on 15 January, while older participants will meet on Thursday 16 January at 7 pm at the Princess Grace Theatre, for our session on Love, desire and sexuality, presented by Robert Maggiori, who will be accompanied by Fabienne Brugère, Emma Becker and Samuel Dock.

Informations

Similar events

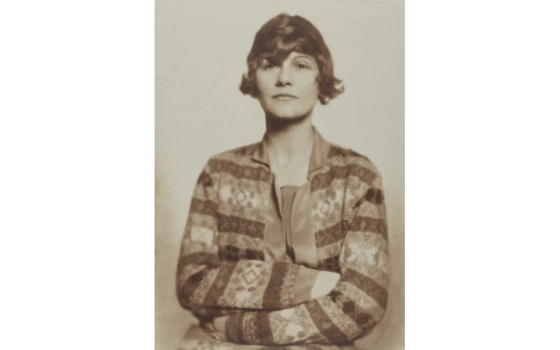

Stages jeune public - Exposition "Les Années folles de Coco Chanel"

Couleurs ! Chefs-d'oeuvre du Centre Pompidou : Visites Contées & Arts Plastiques